Liver and Onions

Reprinted from Zest! the food writing section of Pangyrus literary magazine.

In third grade, I was assigned as homework to prepare my favorite meal for my family. I chose to make liver and onions. An odd selection for an eight-year old, but my experience with food was limited. My mother’s spice cabinet contained salt, paprika, dried minced onions and garlic powder. When I first saw an actual head of garlic, I remember being surprised. I had assumed that garlic, like salt, came only in shaker form.

Feeding our family, which my mother unfailingly did, was not her favorite thing. Between work, kids, and keeping the house going, she was always in a rush. She broiled everything because it was fast. Chicken legs with leathery skin, steaks done past well, and hamburgers with no hint of pink but broiled liver was special. That, she smothered, under a heaping mountain of sautéed onions.

So together we peeled and sliced, then slid the onions into nearly smoking oil. She handled the slippery slab of calf liver and flipped it after ten minutes to ensure a consistent chewy texture. She did most of the work, but when we ate, she praised me for my contribution. I was as proud as if I’d done it all

My first cookbook. I still love the cover.

Something about the transformation from raw ingredients to meals spoke to me. By high school, my mother became my sous chef. If I said, “Chop,” she asked, “How small?” I planned our weekly menu and we shopped for food together. My mother was thrilled to offload the chore and, I now suspect, spend time with her usually cranky teenager. I couldn’t, or to be honest, wouldn’t talk to my mother about things that were going on in my adolescent and young-adult life. I’m sure she had her own private struggles but no matter what we faced in each of our lives, preparing a meal together was wonderfully ordinary. Chop, cook, eat, clean, repeat.

For her, a learning disability made translating written instructions into action a tortuous endeavor. My ability to interpret recipes and transform ingredients into meals was magic to her. Her ability to pick up a bag of flour and estimate, within a tablespoon, how much was left was magic to me. She marveled as my skills improved, and my recipe repertoire moved to delicate butter sauces and soufflés. I marveled at how she fit every plate and bowl in the dishwasher and how, even at a crowded table, she always found room for one more.

If daily meals were not my mother’s forté, cooking for crowds was. My mother collected people. New to the synagogue? Come for dinner. No place to go for Thanksgiving? There’s plenty of soup. Menus were simple, but plentiful. She sectioned bushels of citrus for never-ending fruit salad. Tuna fish, deviled eggs, and always Margie’s noodle kugel, a tribute to her dear friend who died of cancer at thirty-seven, the tragedy of which I didn’t fully understand until I’d reached that age myself.

I think she was happiest when she hosted. Smiling, slightly harried, telling jokes, laughing, never stopping. It wasn’t about the food for her. It was her way of showing she cared. Her reward was that moment when others understood they were important and special. She gave them that moment and in return received one of her own. When she fed others, she nourished herself.

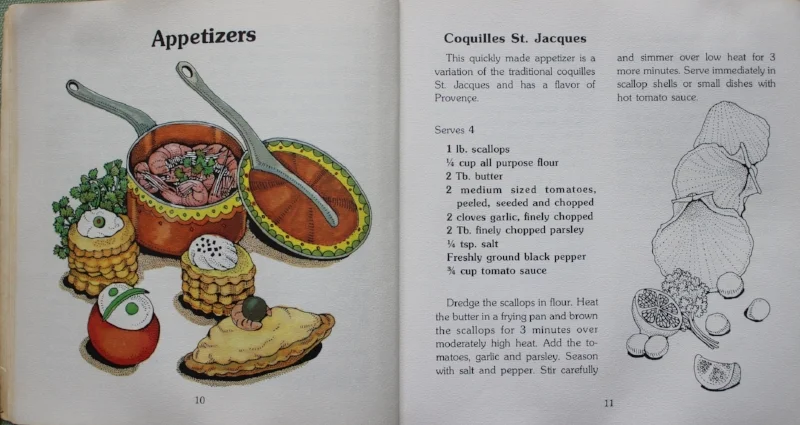

Most pages had colorful illustrations. Recipes were straight forward and for 12 year-old me, extremely fancy.

From the very beginning, food was a bond between us. My mother nursed me and my sisters. It wasn’t easy. Experts of the 1960’s proclaimed science had improved upon nature but she chose to ignore them and gave herself to us in this most elemental way. She told us stories of breast feeding in bathrooms and how her own mother and sisters thought her ridiculous. One of my favorite pictures of her is a black and white snapshot. She is twenty-six and sitting in a car. Her head is tilted slightly to the side and her eyes are sleepy. Just out of frame is my newborn sister having breakfast.

In my family, we never spoke the words aloud. I said, I love you with chocolate-glazed profiteroles and creamy quiche with flaky crust. My mother said them back by buying me illustrated cookbooks and my first chef’s knife. Over time, the number of knives in my canvas roll increased but there was always a special slot for that ten-inch blade with the black plastic handle that I carried to cooking school, to every restaurant I ever worked in, and back home again. I never imagined our time together would end so abruptly, but life, unlike a well-practiced recipe, is unpredictable.

My second cookbook by nitty gritty productions. Gotta love the '70s.

When she was diagnosed with stage-four cancer at fifty-eight, all I could do was sit with her and hold her hand. Chemo made her nauseous and everything she ate tasted metallic. Then one day she asked for my pizza and my chocolate pudding and my homemade bread. I rushed home and turned out dish after dish. I wanted to care for her at the end of her life as she had cared for me at the beginning of mine.

At the hospital she took one bite of each then pushed them away. An oncology nurse told me it was common. Dying patients wanted to taste their favorite foods one last time. It helped them, she said, to make peace with what they were leaving behind. I had, irrationally, wanted what I’d desperately prepared to miraculously heal my mother. Instead, what I’d created helped her to say goodbye.

Now that I have a family of my own, I make sure to say the words but, like my mother, I show how much I love them. When my children were old enough, I taught them to cook. They use the knife my mother gave me forty years before. Though the steel is whittled and liver will never be on the menu, when they chop onions, I shed a tear, not because I’m sad, but because I see in them what my mother saw in me and, if they’re very lucky, what they may someday see in children of their own.

Though she never met my two girls, I believe my children know my mother through the indelible lessons she instilled in me. Deeds speak louder than words, be generous and kind toward others and, maybe the most important and difficult lesson of all: Though love is infinite, time, regrettably, is not.

Those two look like they're enjoying their feast of Chicken-Zucchini Casserole!